Climate Impacts in the Northeast

On This Page:

Overview

The Northeast is home to historic cities and large rural areas that serve as important natural habitats and agricultural lands. Climate varies widely across the region and tends to be coldest in the north, at high elevations, and away from the coast.

The Northeastern climate is experiencing noticeable changes that are expected to increase in the future. Between 1895 and 2011, temperatures rose by almost 2°F and projections indicate warming of 4.5°F to 10°F by the 2080s.[1] The frequency, intensity, and length of heat waves is also expected to increase. The total amount of precipitation and the frequency of heavy precipitation events has also risen in the region.[1] Between 1958 and 2012, the Northeast saw more than a 70% increase in the amount of rainfall measured during heavy precipitation events, more than in any other region in the United States.[2] Projections indicate continuing increases in precipitation, especially in winter and spring and in northern parts of the region. However, the timing of winter and spring precipitation could lead to drought conditions in summer as warmer temperatures increase evaporation and accelerate snow melt.

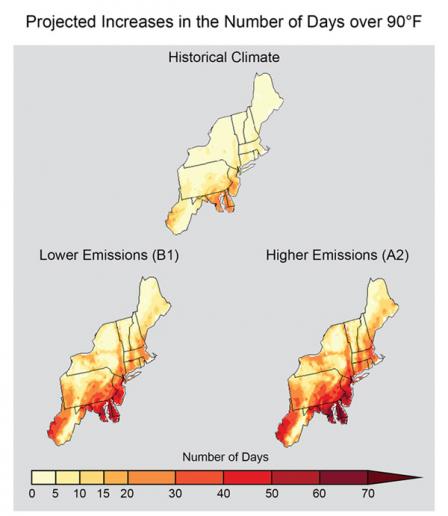

The annual number of days above 90°F is projected to increase, especially for southern portions of the Northeast region. This figure shows the average number of days with a maximum temperature of at least 90°F historically (1971-2000) and under two potential future scenarios (one with reduced greenhouse gas emissions [B1], and one with increases in emissions [A2]). Source: USGCRP (2014)[1]

The annual number of days above 90°F is projected to increase, especially for southern portions of the Northeast region. This figure shows the average number of days with a maximum temperature of at least 90°F historically (1971-2000) and under two potential future scenarios (one with reduced greenhouse gas emissions [B1], and one with increases in emissions [A2]). Source: USGCRP (2014)[1]

Impacts on Human Health

Higher temperatures in the Northeast are likely to increase heat-related deaths and decrease air quality, especially in urban areas.[1] People at greatest risk include young children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing health conditions like asthma. Those who live alone or in low income communities are also at increased risk, particularly if individuals do not have access to air conditioning or are in poor health.[1] Increased strains on cooling infrastructure and greater energy demand could also affect access to air conditioning during heatwaves. Residents in urban areas may experience even warmer temperatures because of the heat island effect, in which metropolitan areas are significantly warmer due to dense populations and human activity. Residents in rural areas are also at high risk because of more buildings and homes without air conditioning.[1]

Studies indicate that climate change is lengthening the pollen season of common allergens such as ragweed, particularly for northern portions of the U.S.[1] Warmer and wetter conditions may increase seasonal activity and the extent of suitable habitat for ticks and mosquitoes, elevating risks of human exposure to vector-borne diseases like Lyme disease and West Nile Virus.[1] More frequent extreme precipitation events and flooding could increase the risk of injury or death, exposure to waterborne illnesses, and reduced access to clean water.[1][3]

For more information about the impacts of climate change on human health, please visit the Health page.

Impacts on Precipitation and Sea Level Rise

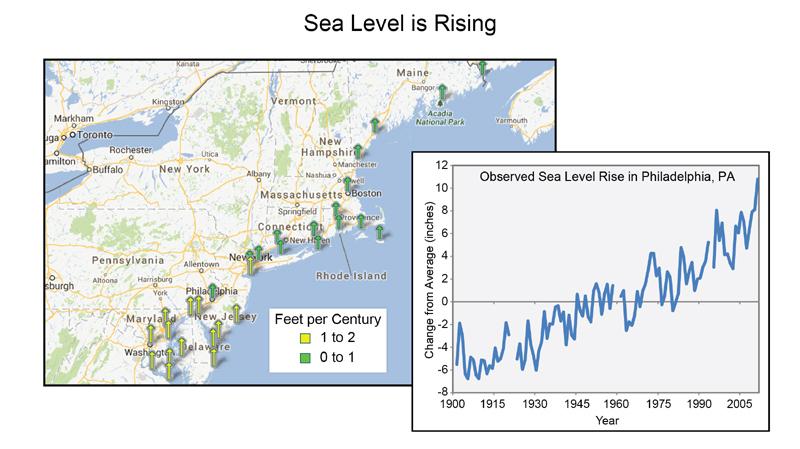

Observed trends indicate an rise in sea level along Northeastern shorelines. (Figure source: NOAA). In Philadelphia, PA, sea level rose 1.2 feet between 1901 and 2012. Source: USGCRP (2014)[1]

Observed trends indicate an rise in sea level along Northeastern shorelines. (Figure source: NOAA). In Philadelphia, PA, sea level rose 1.2 feet between 1901 and 2012. Source: USGCRP (2014)[1]

Click the image to view a larger version.Sea level rise, heavy precipitation, and storm surge are expected to increase flooding and coastal erosion, and put further strain on aging infrastructure in the Northeast.[1] Millions of Northeastern residents live near coastlines and river floodplains, where they are potentially more vulnerable to these climate-related impacts. During storm events with heavy precipitation, combined sewer-stormwater systems in this region can overload, resulting in wastewater discharge into bodies of water used for recreation or drinking water and creating health risks.[1]

In the Northeast, sea level has risen by approximately 1 ft since 1900, which has caused more frequent flooding of coastal areas.[1] Globally, sea level is projected to rise by 1 to 4 ft by the end of this century. In the Northeast, even higher sea level rise is possible, due to the combined effects of warming waters and local land subsidence (sinking). Sea level rise and coastal flooding are likely to disrupt and damage important infrastructure, including communication systems, energy production, transportation, waste management, and access to clean water.[1] These impacts could have large economic implications across this region. In Boston, Massachusetts, the increase in flooding caused by sea level rise this century could cost up to $94 billion from damage to buildings, loss of building contents, and associated emergency activities, depending on the amount of sea level rise and adaptation measures taken.[1]

For more information on climate change impacts on coastal resources, please visit the Coastal page.

Impacts on Agriculture

Climate change is affecting agricultural production in the Northeast. Heavy precipitation events can damage crops and wetter springs may delay planting, resulting in later harvest and reduced yields.[1] Longer, drier summers may reduce water availability and increase plant heat stress, also reducing yields. Warmer spring temperatures may be followed by cold snaps, causing frost damage, while warmer winters and longer growing seasons may increase pressure from weeds and pests.[1] These challenges are likely to affect the types of crops cultivated in the Northeast, as large portions of the region may become unsuitable for growing fruits, like apples and blueberries, and other crops, like grain and soybean.[4]

Dairy production is important to the Northeast's agricultural economy and is expected to be negatively affected by increasing temperatures.[4] Warmer conditions cause heat stress in farm animals, reducing milk yields and calf birth rates. Projected warming temperatures could also increase operations and production costs alongside reductions in milk and meat production.[4]

Fisheries are likely to be harmed by climate change. Many commercially important species are projected to move northward as the region's warming habitats become less suitable.[1] This shift in location is expected to cause local declines in species including lobster and cod. New diseases may also reduce the populations of fisheries. For example, a bacterial shell disease that infects lobsters is currently limited by low water temperatures in the northern portion of the Northeast.[4] Warming waters may allow this disease to move northward causing reduced catch, similar to what has been observed in southern parts of the region.

For more information about the impacts of climate change on agriculture and food supplies, please visit the Agriculture and Food Supply page.

Impacts on Ecosystems

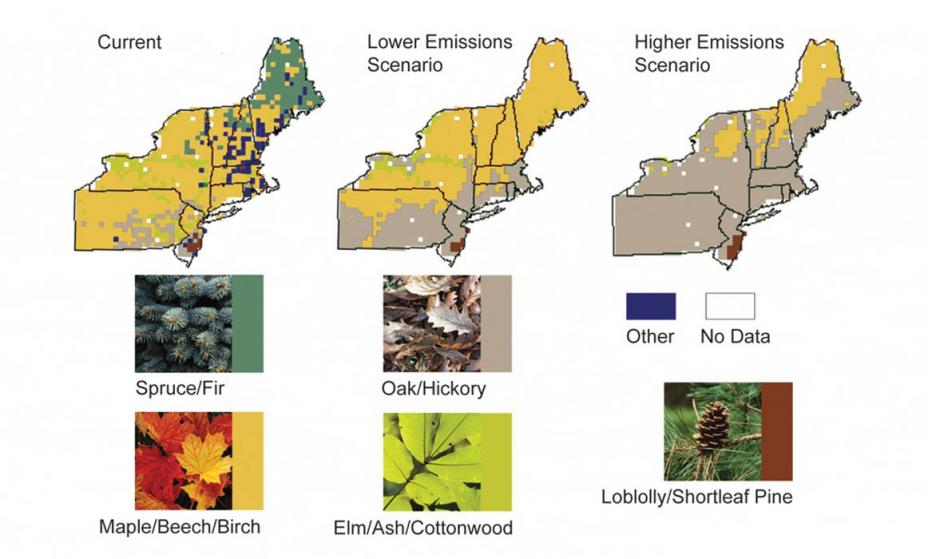

The Northeast is home to a diverse mixture of species and ecosystems that are affected by climate change. Ranges of certain tree species are moving northward and to higher elevations where temperatures are cooler.[1][4] The range of economically important tree species, like sugar maple, is expected to shrink within the U.S. as its preferred climate shifts north into Canada. Warmer temperatures are also increasing outbreaks of forests pests and pathogens, including hemlock woolly adelgid.[1] Growing deer populations have been degrading forest understories, while invasive plants like kudzu have been expanding their range and contributing to a loss of biodiversity, function, and resilience in some ecosystems.[1]

Temperature changes also influence the timing of important ecological events, causing birds to migrate sooner and plants to bloom and leaf earlier.[1] Climate change and sea level rise are expected to harm coastal ecosystems, causing declines in water quality, increasing harmful algal blooms, and shrinking marsh habitat.[1]

For more information about the impacts of climate change on ecosystems, please visit the Ecosystems and Forests page.

Tree species in the Northeast are shifting northward. The range of spruce/fir, maple, and elm/ash/cottonwood forests are shrinking and being replaced by oak/hickory forest in most of the region, and by loblolly/shortleaf pine forest in the southernmost areas. Source: USGCRP (2009)[4]

Tree species in the Northeast are shifting northward. The range of spruce/fir, maple, and elm/ash/cottonwood forests are shrinking and being replaced by oak/hickory forest in most of the region, and by loblolly/shortleaf pine forest in the southernmost areas. Source: USGCRP (2009)[4]

Impacts on Winter Recreation

Winter recreational snow and ice activities generate about $7.6 billion for the Northeast economy annually.[4] These activities include snow sports (skiing, snowmobiling, snowshoeing, dog sledding) and ice-based activities (ice fishing and skating).[4] Projected increases in temperature could reduce snow cover and shorten winter snow seasons, limiting and altering these activities.

In order for ski resorts to remain viable in the Northeast, the average length of the ski season should be at least 100 days, nights must be cold enough to allow for artificial snowmaking, and there must usually be snow during winter holidays when winter tourism is high.[4] Projections indicate that marginal ski resorts in the region will likely close and most resorts will be vulnerable by the end of the century because temperatures will become too warm to meet these criteria. Resorts are likely to require more artificial snowmaking to produce snowpack, employing additional water and energy and increasing costs to the resorts.[4]

References

[1] USGCRP (2014). Horton, R., G. Yohe, W. Easterling, R. Kates, M. Ruth, E. Sussman, A. Whelchel, D. Wolfe, and F. Lipschultz, 2014: Ch. 16: Northeast. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program.

[2] USGCRP (2014) Walsh, J., D. Wuebbles, K. Hayhoe, J. Kossin, K. Kunkel, G. Stephens, P. Thorne, R. Vose, M. Wehner, J. Willis, D. Anderson, S. Doney, R. Feely, P. Hennon, V. Kharin, T. Knutson, F. Landerer, T. Lenton, J. Kennedy, and R. Somerville, 2014: Ch. 2: Our Changing Climate. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 19-67.

[3] USGCRP (2014). Luber, G., K. Knowlton, J. Balbus, H. Frumkin, M. Hayden, J. Hess, M. McGeehin, N. Sheats, L. Backer, C. B. Beard, K. L. Ebi, E. Maibach, R. S. Ostfeld, C. Wiedinmyer, E. Zielinski-Gutirrez, and L. Ziska, 2014: Ch. 9: Human Health. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 220-256.

[4] USGCRP (2009). Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. Karl, T. R., J. M. Melillo, and T. C. Peterson (eds.). United States Global Change Research Program. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA.