Climate Change Indicators: Ocean Heat

This indicator describes trends in the amount of heat stored in the world’s oceans.

-

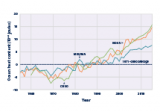

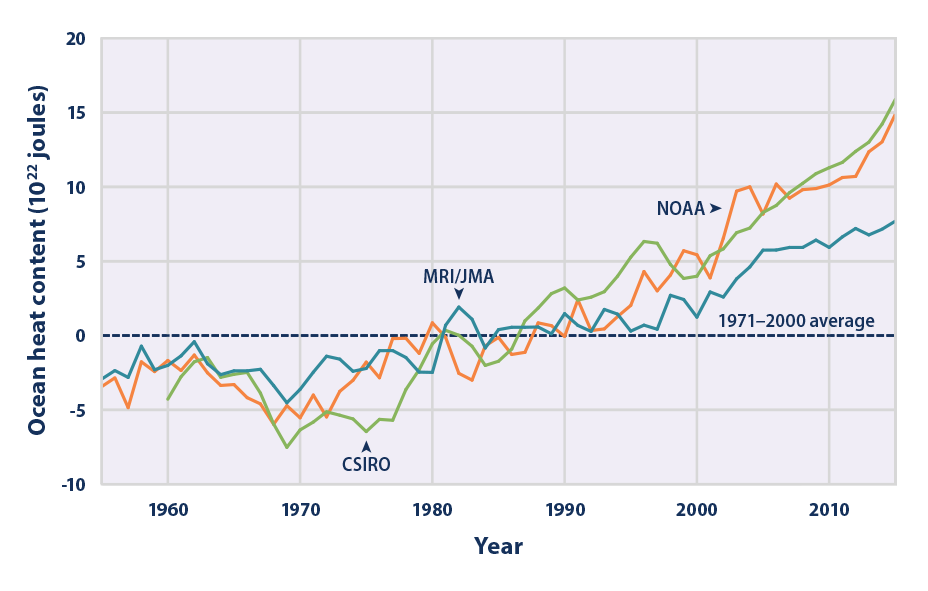

This figure shows changes in ocean heat content between 1955 and 2015. Ocean heat content is measured in joules, a unit of energy, and compared against the 1971–2000 average, which is set at zero for reference. Choosing a different baseline period would not change the shape of the data over time. The lines were independently calculated using different methods by government agencies in three countries: the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), and Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute (MRI/JMA). For reference, an increase of 1 unit on this graph (1 x 1022 joules) is equal to approximately 18 times the total amount of energy used by all the people on Earth in a year.4

Data sources: CSIRO, 20165; MRI/JMA, 20166; NOAA, 20167

Web update: August 2016

Key Points

- In three different data analyses, the long-term trend shows that the oceans have become warmer since 1955 (see Figure 1).

- Although concentrations of greenhouse gases have risen at a relatively steady rate over the past few decades (see the Atmospheric Concentrations of Greenhouse Gases indicator), the rate of change in ocean heat content can vary from year to year (see Figure 1). Year-to-year changes are influenced by events such as volcanic eruptions and recurring ocean-atmosphere patterns such as El Niño.

Background

When sunlight reaches the Earth’s surface, the world’s oceans absorb some of this energy and store it as heat. This heat is initially absorbed at the surface, but some of it eventually spreads to deeper waters. Currents also move this heat around the world. Water has a much higher heat capacity than air, meaning the oceans can absorb larger amounts of heat energy with only a slight increase in temperature.

The total amount of heat stored by the oceans is called “ocean heat content,�? and measurements of water temperature reflect the amount of heat in the water at a particular time and location. Ocean temperature plays an important role in the Earth’s climate system—particularly sea surface temperature (see the Sea Surface Temperature indicator)—because heat from ocean surface waters provides energy for storms and thereby influences weather patterns.

Increasing greenhouse gas concentrations are trapping more energy from the sun. Because changes in ocean systems occur over centuries, the oceans have not yet warmed as much as the atmosphere, even though they have absorbed more than 90 percent of the Earth’s extra heat since 1955.1,2 If not for the large heat-storage capacity provided by the oceans, the atmosphere would warm more rapidly.3 Increased heat absorption also changes ocean currents because many currents are driven by differences in temperature, which cause differences in density. These currents influence climate patterns and sustain ecosystems that depend on certain temperature ranges.

Because water expands slightly as it gets warmer, an increase in ocean heat content will also increase the volume of water in the ocean, which is one cause of the observed increases in sea level (see the Sea Level indicator).

About the Indicator

This indicator shows trends in global ocean heat content from 1955 to 2015. These data are available for the top 700 meters of the ocean (nearly 2,300 feet), which accounts for just under 20 percent of the total volume of water in the world’s oceans. The indicator measures ocean heat content in joules, which are units of energy.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has calculated changes in ocean heat content based on measurements of ocean temperatures around the world at different depths. These measurements come from a variety of instruments deployed from ships and airplanes and, more recently, underwater robots. Thus, the data must be carefully adjusted to account for differences among measurement techniques and data collection programs. Figure 1 shows three independent interpretations of essentially the same underlying data.

Indicator Notes

Data must be carefully reconstructed and filtered for biases because of different data collection techniques and uneven sampling over time and space. Various methods of correcting the data have led to slightly different versions of the ocean heat trend line. Scientists continue to compare their results and improve their estimates over time. They also test their ocean heat estimates by looking at corresponding changes in other properties of the ocean. For example, they can check to see whether observed changes in sea level match the amount of sea level rise that would be expected based on the estimated change in ocean heat.

Data Sources

Data for this indicator were collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other organizations around the world. The data were analyzed independently by researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute.

Technical Documentation

References

1. IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2013. Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Working Group I contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg1.

2. Levitus, S., J.I. Antonov, T.P. Boyer, O.K. Baranova, H.E. Garcia, R.A. Locarnini, A.V. Mishonov, J.R. Reagan, D. Seidov, E.S. Yarosh, and M.M. Zweng. 2012. World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (0–2000 m), 1955–2010. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39:L10603.

3. Levitus, S., J.I. Antonov, T.P. Boyer, O.K. Baranova, H.E. Garcia, R.A. Locarnini, A.V. Mishonov, J.R. Reagan, D. Seidov, E.S. Yarosh, and M.M. Zweng. 2012. World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (0–2000 m), 1955–2010. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39:L10603.

4. Based on a total global energy supply of 13,541 million tons of oil equivalents in the year 2013, which equates to 5.7 x 1020 joules. Source: IEA (International Energy Agency). 2015. Key world energy statistics. www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/KeyWorld_Statistics_2015.pdf.

5. CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation). 2016 update to data originally published in: Domingues, C.M., J.A. Church, N.J. White, P.J. Gleckler, S.E. Wijffels, P.M. Barker, and J.R. Dunn. 2008. Improved estimates of upper-ocean warming and multi-decadal sea-level rise. Nature 453:1090–1094. www.cmar.csiro.au/sealevel/thermal_expansion_ocean_heat_timeseries.html.

6. MRI/JMA (Meteorological Research Institute/Japan Meteorological Agency). 2016 update to data originally published in: Ishii, M., and M. Kimoto. 2009. Reevaluation of historical ocean heat content variations with time-varying XBT and MBT depth bias corrections. J. Oceanogr. 65:287–299.

7. NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2016. Global ocean heat and salt content. Accessed May 2016. www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/3M_HEAT_CONTENT.