Climate Change Indicators: Heat-Related Deaths

This indicator presents data on deaths classified as “heat-related� in the United States.

-

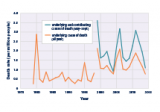

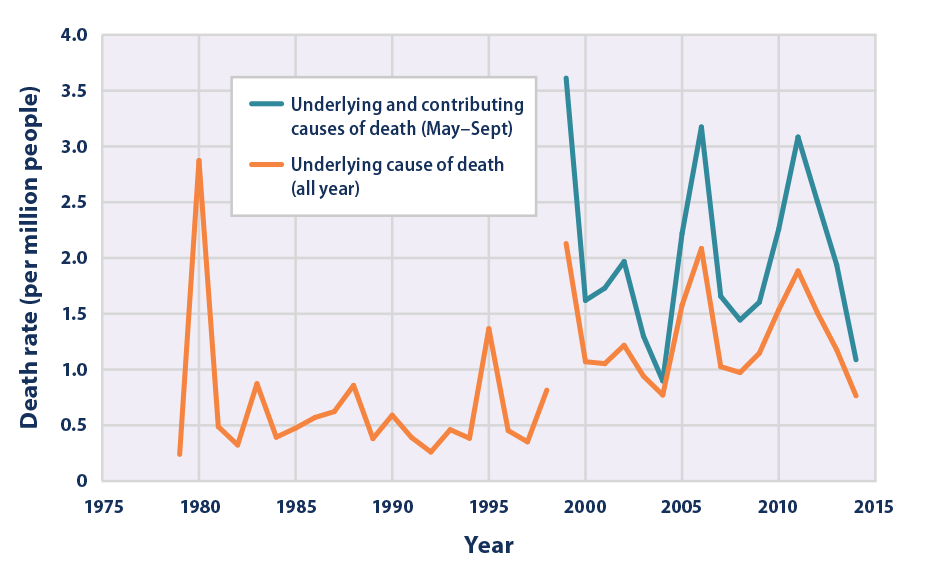

This figure shows the annual rates for deaths classified as “heat-related� by medical professionals in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The orange line shows deaths for which heat was listed as the main (underlying) cause.* The blue line shows deaths for which heat was listed as either the underlying or contributing cause of death during the months from May to September, based on a broader set of data that became available in 1999.

* Between 1998 and 1999, the World Health Organization revised the international codes used to classify causes of death. As a result, data from earlier than 1999 cannot easily be compared with data from 1999 and later.

-

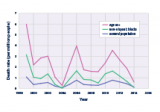

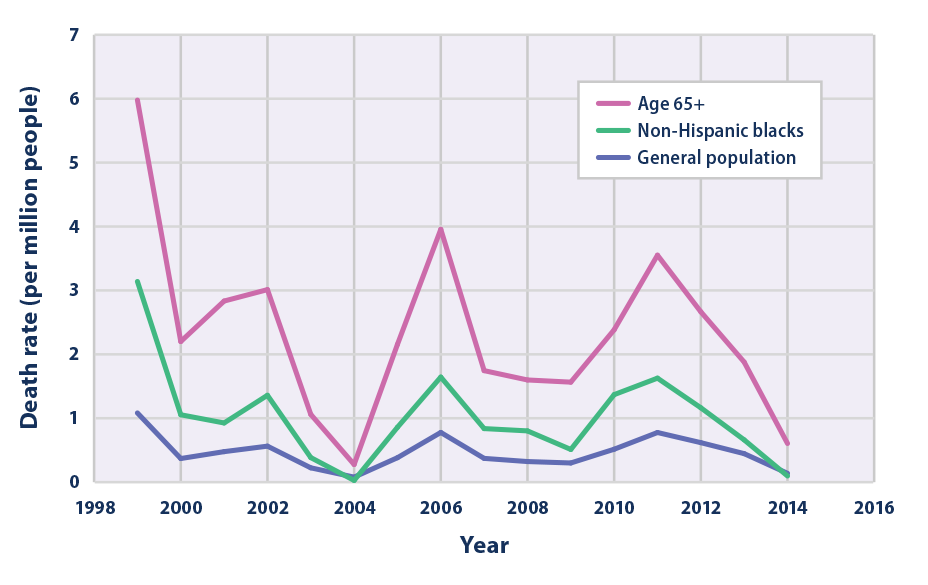

This figure shows rates for deaths that medical professionals have classified as being caused by a combination of cardiovascular disease (diseases of the circulatory system) and heat exposure. This graph presents summer (May to September) death rates from 1999 to 2014 for three population groups in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The purple line shows rates for the entire population, the green line shows rates for non-Hispanic black people, and the pink line shows rates for people aged 65 and older.

Data source: CDC, 201611

Web update: August 2016 -

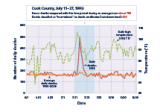

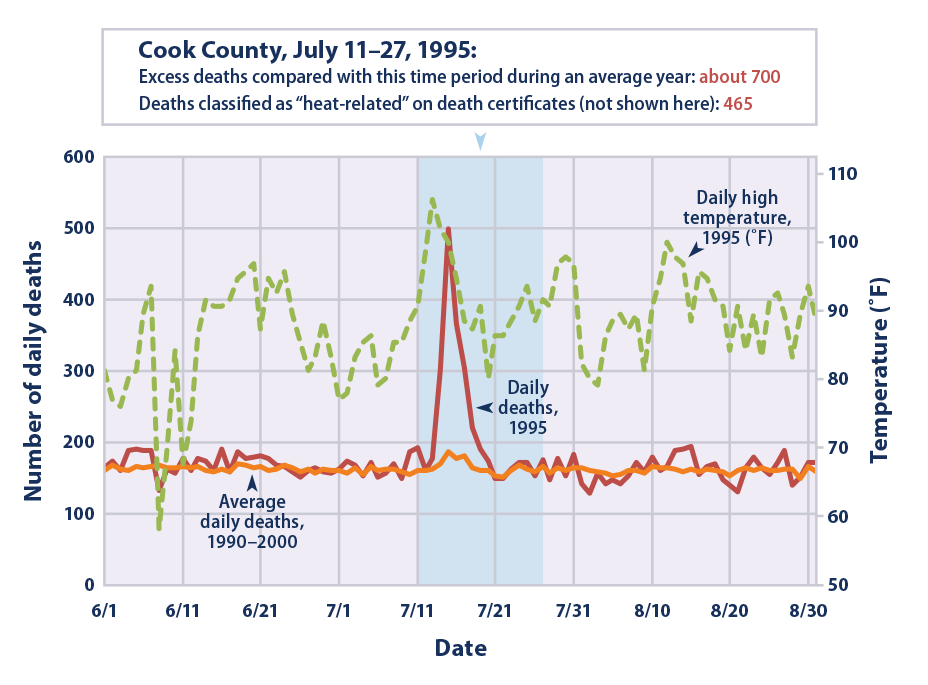

Many factors can influence the nature, extent, and timing of health consequences associated with extreme heat events.12Â Studies of heat waves are one way to better understand health impacts, but different methods can lead to very different estimates of heat-related deaths. For example, during a severe heat wave that hit Chicago* between July 11 and July 27, 1995, 465 heat-related deaths were recorded on death certificates in Cook County.13Â However, studies that compared the total number of deaths during this heat wave (regardless of the recorded cause of death) with the long-term average of daily deaths found that the heat wave likely led to about 700 more deaths than would otherwise have been expected.14Â Differences in estimated heat-related deaths that result from different methods may be even larger when considering the entire nation and longer time periods.

* This graph shows data for the Chicago Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Data sources: CDC, 2012;15Â NOAA, 201216

Web update: August 2016

Key Points

- Between 1979 and 2014, the death rate as a direct result of exposure to heat (underlying cause of death) generally hovered around 0.5 to 1 deaths per million people, with spikes in certain years (see Figure 1). Overall, a total of more than 9,000 Americans have died from heat-related causes since 1979, according to death certificates.

- For years in which the two records overlap (1999–2014), accounting for those additional deaths in which heat was listed as a contributing factor results in a higher death rate—nearly double for some years—compared with the estimate that only includes deaths where heat was listed as the underlying cause (see Figure 1).

- The indicator shows a peak in heat-related deaths in 2006, a year that was associated with widespread heat waves and was one of the hottest years on record in the contiguous 48 states (see the U.S. and Global Temperature indicator).

- The death rate from heat-related cardiovascular disease ranged from 0.08 deaths per million people in 2004 to 1.08 deaths per million people in 1999 (see Figure 2). Overall, the interaction of heat and cardiovascular disease caused about one-fourth of the heat-related deaths recorded in the “underlying and contributing causes� analysis since 1999 (see Figures 1 and 2).

- Since 1999, people aged 65+ have been several times more likely to die from heat-related cardiovascular disease than the general population, while non-Hispanic blacks generally have had higher-than-average rates (see Figure 2).

- Examination of extreme events has revealed challenges in capturing the full extent of “heat-related� deaths. For example, studies of the 1995 heat wave event in Chicago (see example figure) suggest that there may have been hundreds more deaths than were actually reported as “heat-related� on death certificates.

- While dramatic increases in heat-related deaths are closely associated with the occurrence of hot temperatures and heat waves, these deaths may not be reported as “heat-related� on death certificates. This limitation, as well as considerable year-to-year variability in the data, make it difficult to determine whether the United States has experienced a meaningful increase or decrease in deaths classified as “heat-related� over time.

Background

When people are exposed to extreme heat, they can suffer from potentially deadly illnesses, such as heat exhaustion and heat stroke. Hot temperatures can also contribute to deaths from heart attacks, strokes, and other forms of cardiovascular disease. Heat is the leading weather-related killer in the United States, even though most heat-related deaths are preventable through outreach and intervention (see EPA’s Excessive Heat Events Guidebook at: www.epa.gov/heat-islands/excessive-heat-events-guidebook).

Unusually hot summer temperatures have become more common across the contiguous 48 states in recent decades1 (see the High and Low Temperatures indicator), and extreme heat events (heat waves) are expected to become longer, more frequent, and more intense in the future.2 As a result, the risk of heat-related deaths and illness is also expected to increase.3 Reductions in cold-related deaths are projected to be smaller than increases in heat-related deaths in most regions.4 Death rates can also change, however, as people acclimate to higher temperatures and as communities strengthen their heat response plans and take other steps to continue to adapt.

Certain population groups already face higher risks of heat-related death, and increases in summertime temperature variability will increase that risk.5,6 The population of adults aged 65 and older, which is expected to continue to grow, has a higher-than-average risk of heat-related death. Children are particularly vulnerable to heat-related illness and death, as their bodies are less able to adapt to heat than adults, and they must rely on others to help keep them safe.7 People with certain diseases, such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, are especially vulnerable to excessive heat exposure, as are the economically disadvantaged. Data also suggest a higher risk among non-Hispanic blacks.8

About the Indicator

This indicator shows the annual rate for deaths classified by medical professionals as “heat-related� in the United States based on death certificate records. Every death is recorded on a death certificate, where a medical professional identifies the main cause of death (also known as the underlying cause), along with other conditions that contributed to the death. These causes are classified using a set of standard codes. Dividing the annual number of deaths by the U.S. population in that year, then multiplying by one million, will result in the death rates (per million people) that this indicator shows.

Figure 1 shows heat-related death rates using two methods. One method shows deaths for which excessive natural heat was stated as the underlying cause of death from 1979 to 2014. The other data series shows deaths for which heat was listed as either the underlying cause or a contributing cause, based on a broader set of data that, at present, can only be evaluated back to 1999. For example, in a case where cardiovascular disease was determined to be the underlying cause of death, heat could be listed as a contributing factor because it can make the individual more susceptible to the effects of this disease. Because excessive heat events are associated with summer months, the 1999–2014 analysis was limited to May through September.

Figure 2 offers a closer look at cardiovascular disease deaths for which heat was recorded as a contributing cause. This graph includes deaths due to heart attacks, strokes, and other diseases related to the circulatory system. Figure 2 shows death rates for the overall population as well as two groups with a higher risk: people age 65 and older and non-Hispanic blacks. Like the “underlying and contributing causesâ€? analysis in Figure 1, Figure 2 is restricted to the summer months, and it uses data that are available from 1999 to 2014.Â

Indicator Notes

Several factors influence the ability of this indicator to estimate the true number of deaths associated with extreme heat events. It has been well documented that many deaths associated with extreme heat are not identified as such by the medical examiner and might not be correctly coded on the death certificate. In many cases, the medical examiner might classify the cause of death as a cardiovascular or respiratory disease, not knowing for certain whether heat was a contributing factor, particularly if the death did not occur during a well-publicized heat wave. Furthermore, deaths can occur from exposure to heat (either as an underlying cause or as a contributing factor) that is not classified as extreme and therefore is often not recorded as such. Some statistical approaches estimate that more than 1,300 deaths per year in the United States are due to extreme heat, compared with about 600 deaths per year in the “underlying and contributing causes� data set shown in Figure 1.17 By studying how daily death rates vary with temperature in selected cities, scientists have found that extreme heat contributes to far more deaths than the official death certificates might suggest.18 This is because the stress of a hot day can increase the chance of dying from a heart attack, other heart conditions, or respiratory diseases such as pneumonia.19 These causes of death are much more common than heat-related illnesses such as heat stroke. Thus, this indicator very likely underestimates the number of deaths caused by exposure to heat.

Classifying a death as “heat-related� does not mean that high temperatures were the only factor that caused or contributed to the death, as pre-existing medical conditions can significantly increase an individual’s susceptibility to heat. Other important factors, such as the overall vulnerability of the population, the extent to which people have adapted and acclimated to higher temperatures, and the local climate and topography, can affect trends in heat-related deaths. Heat response measures, such as early warning and surveillance systems, air conditioning, health care, public education, cooling centers, infrastructure standards, and air quality management, can also make a big difference in reducing death rates. For example, after a 1995 heat wave, the city of Milwaukee developed a plan for responding to extreme heat conditions; during a 1999 heat wave, heat-related deaths were roughly half of what would have been expected.20

Future development related to this indicator should focus on capturing all heat-related deaths, not just those with a reported link to heat stress.

Data Sources

Data for this indicator were provided by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The 1979–2014 underlying cause data in Figure 1 are publicly available through the CDC WONDER database at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html. The 1999–2014 analysis in Figure 1 was developed by CDC’s Environmental Public Health Tracking Program, which provides a summary at: www.cdc.gov/nceh/tracking. The cardiovascular disease data in Figure 2 are publicly available through the CDC WONDER database at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html.

Technical Documentation

References

1Â Melillo, J.M., T.C. Richmond, and G.W. Yohe (eds.). 2014. Climate change impacts in the United States: The third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. http://nca2014.globalchange.gov.

2 Melillo, J.M., T.C. Richmond, and G.W. Yohe (eds.). 2014. Climate change impacts in the United States: The third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. http://nca2014.globalchange.gov.

3 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2014. Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Working Group II contribution to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2.

4 Sarofim, M.C., S. Saha, M.D. Hawkins, D.M. Mills, J. Hess, R. Horton, P. Kinney, J. Schwartz, and A. St. Juliana. 2016. Chapter 2: Temperature-related death and illness. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://health2016.globalchange.gov.

5 Zanobetti, A., M.S. O’Neill, C.J. Gronlund, and J.D. Schwartz. 2012. Summer temperature variability and long-term survival among elderly people with chronic disease. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109(17):6608–6613.

6 Sarofim, M.C., S. Saha, M.D. Hawkins, D.M. Mills, J. Hess, R. Horton, P. Kinney, J. Schwartz, and A. St. Juliana. 2016. Chapter 2: Temperature-related death and illness. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://health2016.globalchange.gov.

7 USGCRP, 2016: The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment. Crimmins, A., J. Balbus, J.L. Gamble, C.B. Beard, J.E. Bell, D. Dodgen, R.J. Eisen, N. Fann, M.D. Hawkins, S.C. Herring, L. Jantarasami, D.M. Mills, S. Saha, M.C. Sarofim, J. Trtanj, and L. Ziska, Eds. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, 312 pp.  http://dx.doi.org/10.7930/J0R49NQX

8 Berko, J., D.D. Ingram, S. Saha, and J.D. Parker. 2014. Deaths attributed to heat, cold, and other weather events in the United States, 2006–2010. National Health Statistics Reports, Number 76. National Center for Health Statistics. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr076.pdf.

9 CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2016. CDC WONDER database: Compressed mortality file, underlying cause of death. Accessed February 2016. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html.

10 CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2016. Indicator: Heat-related mortality. National Center for Health Statistics. Annual national totals provided by National Center for Environmental Health staff in June 2016. http://ephtracking.cdc.gov/showIndicatorPages.action.

11 CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2016. CDC WONDER database: Multiple cause of death file. Accessed July 2016. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html.

12 Anderson, G.B., and M.L. Bell. 2011. Heat waves in the United States: Mortality risk during heat waves and effect modification by heat wave characteristics in 43 U.S. communities. Environ. Health Persp. 119(2):210–218.

13 CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1995. Heat-related mortality—Chicago, July 1995. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 44(31):577–579.

14 NRC (National Research Council). 2011. Climate stabilization targets: Emissions, concentrations, and impacts over decades to millennia. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

15 CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2012. CDC WONDER database. Accessed August 2012. http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html.

16 NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2012. National Centers for Environmental Information. Accessed August 2012. www.ncdc.noaa.gov.

17 Sarofim, M.C., S. Saha, M.D. Hawkins, D.M. Mills, J. Hess, R. Horton, P. Kinney, J. Schwartz, and A. St. Juliana. 2016. Chapter 2: Temperature-related death and illness. The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://health2016.globalchange.gov.

18 Medina-Ramón, M., and J. Schwartz. 2007. Temperature, temperature extremes, and mortality: A study of acclimatization and effect modification in 50 U.S. cities. Occup. Environ. Med. 64(12):827–833.

19 Kaiser, R., A. Le Tertre, J. Schwartz, C.A. Gotway, W.R. Daley, and C.H. Rubin. 2007. The effect of the 1995 heat wave in Chicago on all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Am. J. Public Health 97(Supplement 1):S158–S162.

20 Weisskopf, M.G., H.A. Anderson, S. Foldy, L.P. Hanrahan, K. Blair, T.J. Torok, and P.D. Rumm. 2002. Heat wave morbidity and mortality, Milwaukee, Wis., 1999 vs. 1995: An improved response? Am. J. Public Health 92:830–833.